Originally published on Ussporthistory.com

Boxing has long been a sport for the lower-classes which, for most of its early history was illegal and practiced in secrecy to avoid arrests. However in the late 1800s there was a change in who practiced boxing. This shift came from a variety of reasons including a movement away from the Victorian Age virtues and an increasing concern that white American men were becoming increasingly effeminate due to a perceived over-civilization. Adding to boxing’s new-found societal acceptance was the drastic changes that came in 1889 from the Marquess de Queensbury rules replacing the London Prize Ring Rules. The new rules disallowed hugging and wrestling, placed three-minute limits on rounds, added a ten-second count after each knock down, and most importantly, called for gloved fists. Essentially, the new rules brought an end to boxing’s days of bareknuckle fights.

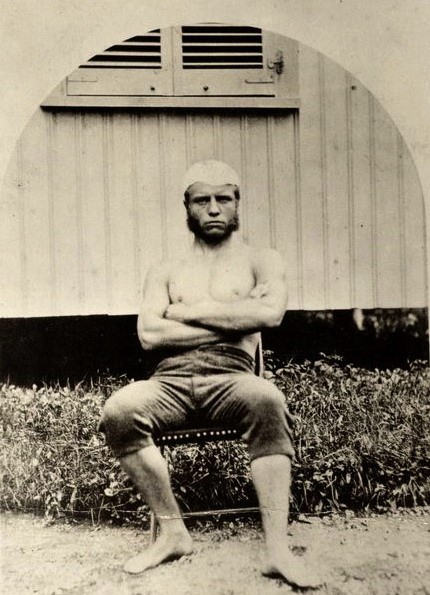

As the upper-classes increasingly took part in the sport, a few athletic clubs hired ex-bareknuckle boxers to show their elite members the intricacies of the sweet science. One of these instructors was “The Professor” Mike Donovan, who gained his nickname for his technical mastery of the sport. The New York Athletic Club hired Donovan to teach the same sport to upper-class clientele that in earlier generations considered it too barbaric and offensive to their moral sensibilities. These same people now praised boxing’s virtues, seeing it as a way of instilling self-confidence and courage. In boxing’s ascent towards social acceptance, it was not as if it was without its critics. But rather, for the first time in decades, boxing’s positives outweighed its negatives. And although “the ends of prize fighting might be corrupt…the means were divine, for hard training brought boxers to physical and mental perfection.”[1]

Speaking to boxing’s popularity, acceptance, and fear that the upper-classes were going soft, elite universities instituted boxing programs. Theodore Roosevelt was one of these boxing student-athletes as part of Harvard’s boxing club. “I did a good deal of boxing and wrestling in Harvard,” Roosevelt recalled in his autobiography, “but never attained to the first rank in either, even at my own weight.”[2] Regardless of his level of competency, Roosevelt boxed even after Harvard, becoming a close friend and pupil of Mike Donovan. At one point, Roosevelt even sparred inside the White House. And instead of sparring only as a way to stay physically active, Roosevelt took the sessions seriously, at one point being punched so hard that his left eye’s retina detached, losing sight in that eye.[3] Government authorities kept the injury a secret for more than a decade. Upon finding out of Roosevelt’s blindness The Richmond Times-Dispatch dedicated an entire page to the story. They wrote, “The American public has just been startled by the discovery that its most strenuous citizen, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, had long lost the sight of his left eye.” After losing the use of his left eye, Roosevelt stopped boxing. In a letter to Pierre de Coubertin—French educator and known as the father of the modern Olympic games—Roosevelt explained why he spent less time boxing: “I do but little boxing because it seems rather absurd for a President to appear with a black eye or a swollen nose or a cut lip.”[4]

Yet, boxing’s newfound acceptance—even being practiced in the White House—would not last. Criticism resumed, gaining momentum after Jack Johnson became the first black heavyweight champion. Despite his connections to the sport, Roosevelt became an important voice against boxing. In 1910, after Jack Johnson defeated Jim Jeffries, the latest of the so-called “Great White Hopes,” Roosevelt stated, “The last contest provoked a very unfortunate display of race antagonism. I sincerely trust that public sentiment will be so aroused, and will make itself felt so effectively, as to guarantee that this is the last prize fight to take place in the United States.”[5] Although prize fighting continued, Roosevelt was right about one thing—the fight produced “race antagonism,” as he mildly put it. A more apt description would be race riots, resulting in the death of six black people and many others injured as violence erupted across the country after Johnson beat Jeffries.

In making his declaration against boxing, Roosevelt conveniently forgot that a year earlier he welcomed the lightweight boxing champion Oscar “The Battling Nelson” Nielsen—who was white—into the White House as his guest, even sending him away with an autographed photo.[6] But with Johnson as champion, the problem with boxing suddenly became a racial one. W.E.B. Du Bois, a contemporary of Johnson and one of the most influential black voices stated, “Boxing has fallen into disfavor…The cause is clear: Jack Johnson…Neither he nor his race invented prize fighting or particularly like it. Why then this thrill of national disgust? Because Johnson is black…Wherefore we conclude that at present prize fighting is very, very immoral … until Mr. Johnson retires or permits himself to be ‘knocked out.’[7]

Du Bois’s words proved prophetic as a year after Johnson lost his title to Jess Willard, Roosevelt returned to advocating for boxing, writing a letter to Robert Fitzsimmons, his friend and former heavyweight champion, encouraging him on his attempt to popularize boxing in Argentina.[8] Roosevelt even offered to help of his son, Kermit, who would introduce Fitzsimmons to “Argentines of the right kind, men interested in sports and physical exercises.”[9] Once Johnson lost the title, and the supposed proper order of things was reset with a white champion, boxing could once again, help the “right kind” of people overcome their masculine insecurities.

In the early parts of the 20th century, boxing—and other “manly” sports, like college football—helped calm the fears that for white men, “oversentimentality, oversoftness, … washiness and mushiness” were grave dangers.[10] At a time of increased foreign encounters, both at home and abroad, this softness and hesitancy prevented the country from fulfilling its self-appointed role atop the racial hierarchy that included the burden of civilizing the barbarous. This was the white man’s burden, epitomized by Rudyard Kipling’s poem by the same name. Indeed, as the two were friends, Kipling sent Roosevelt a copy of “The White Man’s Burden” after he wrote it in 1898. Kipling’s intent was to “encourage the American government to take over the Philippines…and rule it with the same energy, honor, and beneficence that, he believed, characterized British rule over the nonwhite populations of India and Africa.”[11] The poem described the subduing of the “Half-devil and half child” and bringing forth “the savage wars of peace.” And like Rudyard, Roosevelt believed such a task could not be carried out if “the best ye breed” came from an effeminate nation.[12] As Roosevelt wrote, “A nation that cannot fight is not worth its salt, no matter how cultivated and refined it may be.”[13] Logically, a nation’s inability to defend itself put its existence at stake.

And still, under Roosevelt, the county had to find a balance between being over-civilized while still maintaining enough civility to distinguish itself from the savage nations being guided towards progress. For a time—so long as a white man was champion—people like Roosevelt advocated boxing as that balance.

[1] Elliot J. Gorn, The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prizefighting in America (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1986), 199.

[2] Theodore Roosevelt, An Autobiography by Theodore Roosevelt. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/3335/3335-h/3335-h.htm

[3] “How Colonel Roosevelt Lost his Eye,” The Richmond Times-Dispatch, November 4, 1917.

[4] Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Pierre de Coubertin. June 15, 1903 Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

[5] Theodore Roosevelt, “The Recent Prize Fight,” The Outlook, July 16, 1910.

[6] “Battling Nelson at White House.” New-York Tribune, January 15, 1909.

[7] W.E.B. Du Bois “The Prize Fighter.” The Crisis 8, No. 4 August, 1914. Whole No. 46, P. 181. http://library.brown.edu/pdfs/1302701412421878.pdf

[8] Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Robert Fitzsimmons. August 16, 1915. Theodore Roosevelt Collection. MS Am 1541 (257). Harvard College Library. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

[9] Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to Kermit Roosevelt. August 7, 1915 Theodore Roosevelt Collection. MS Am 1541 (257). Harvard College Library. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

[10] Theodore Roosevelt, Letters and Speeches (New York, NY: The Library of America, 2004), 183.

[11] Patrick Brantlinger, “Kipling’s “The White Man’s Burden” and Its Afterlives” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 50 No. 2 (2007): 172.

[12] Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden,” The Writings in Prose and Verse of Rudyard Kipling: The Five Nations (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903), 78.

[13] Theodore Roosevelt, Letters and Speeches (New York, NY: The Library of America, 2004), 183.