On an April day in 1919, American boxer Jack Johnson arrived at Casa de los Azulejos (House of Tiles), a restaurant in Mexico City owned by white American expatriates, the Sanborn brothers. Like many in the U.S. the Sanborn’s believed in segregation and refused to serve Johnson, forcing him to eat elsewhere. As night fell Johnson returned a few hours later accompanied by members of the Mexican military including a few of Venustiano Carranza’s generals and colonels. The waiter took the orders from the party while, again, ignoring Johnson. This time, the service refusal created a commotion escalating into a confrontation between one of the generals and Walter Sanborn.

The generals informed Sanborn that in Mexico, everyone received service regardless of color as “Mexico was not a white man’s country.” Further, in Mexico “there are no color differences, everyone is equal.”[1] The generals drew their guns, threatened Sanborn who continued to refuse service to Johnson. Before police arrived to quell tensions, a crowd gathered outside the restaurant who in recognizing Johnson and realizing what was occurring, chanted, “Viva Johnson, viva Mexico!”[2] Sanborn relented to public pressure, shook Johnson’s hand and served him ice cream. There are various accounts of this story some portraying Johnson in an aggressive manner but each acknowledging Sanborn’s refusal to serve Johnson.[3] Mexico City newspaper, El Universal and a U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating Mexican affairs covered the confrontation which became known as the Sanborn incident.[4]

Significant in the Sanborn incident were the chants of “Viva Johnson, viva Mexico!” This was a remarkable change of events considering four years earlier, Johnson could not arrive in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua for a scheduled fight against Jess Willard. Pancho Villa, who controlled Mexico’s northern territory, intended to fund the fight as a way of generating money for his ongoing revolution against Carranza. With its closeness to the U.S. and Johnson’s popularity on both sides of the border, estimates believed the fight in Ciudad Juárez could attract and accommodate 100,000 people.[5] But since the fight would help Villa’s war chest, Carranza threatened to arrest and return Johnson to the U.S., from where he fled in 1913 after a Mann Act conviction.[6] With Carranza controlling Mexico’s ports and Johnson’s inability to travel to Ciudad Juárez through the U.S., the fight took place in Havana, Cuba.[7]

During the time in which Johnson’s fight was to take place, control of Mexico hung in the balance. In December 1914, Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa arrived in Mexico City at the head of their Southern and Northern military divisions, respectively. An iconic photograph showing Villa and Zapata sitting side by side in the presidential chair, captured the momentous occasion showing a jovial Villa while a somber Zapata simply posed for the photograph. For many, the event marked the height of the Mexican Revolution as its two most recognizable and charismatic leaders occupied the capital. But soon afterwards Villa and Zapata left the capital with Carranza’s troops at their heels. Álvaro Obregón led Carranza’s troops and specifically engaged Villa in various battles throughout his retreat north. After his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Celaya, Villa’s influence on the Mexican Revolution would never be as impactful as during his and Zapata’s brief occupation of Mexico City. As for Zapata, his assassination (orchestrated by Carranza) was the front page story of the same issue of El Universal that covered the Sanborn incident. By 1919 the Mexican Revolution was into its ninth year and as Carranza became Mexico’s constitutional president he consolidated control of the country while the rebels lost their influence.

As the revolution’s violence subsided a sense of peace followed. Further, Carranza and Johnson now considered each other friends, explaining why Mexican generals and colonels came to Johnson’s defense at La Casa de Azulejos.[8] “Frequently we met each other in private,” Johnson wrote on his meetings with Carranza. “At which times we engaged in conversations which ranged over many subjects…He was greatly interested in world politics and in the future relations between his country and the U.S. He questioned me…and drew from me my views on international politics.”[9] Although Johnson admitted he was not a political authority, for Carranza to even meet and talk about politics shows their level of friendship and mutual respect. With Mexico’s political climate and violence stabilized the Sanborn brothers felt comfortable expanding their pharmaceutical business, opening their restaurant in downtown Mexico City. Ultimately the sense of peace was a façade as violence continued, culminating with Carranza’s assassination.

So where does Jack Johnson fit into all of this? The idea of Mexico as a color-blind country and a place where a black man could find refuge from his home country that persecuted him because of his race, sounds great—even heartwarming. But it is much more complicated than that. Through Jack Johnson’s life in revolutionary Mexico we can examine the attitudes towards race in both Mexico and the U.S. We discover that as Jack Johnson attempted to make a life in Mexico, their revolution shaped his level of societal acceptance within the country. As the revolution evolved, the political relationship between Mexico and the U.S. further influenced Johnson’s perception within both governments. And as if marrying white women during the Jim Crow era had not caused enough trouble for Johnson, his time and actions in Mexico added to his already troubling reputation in the U.S.[10]

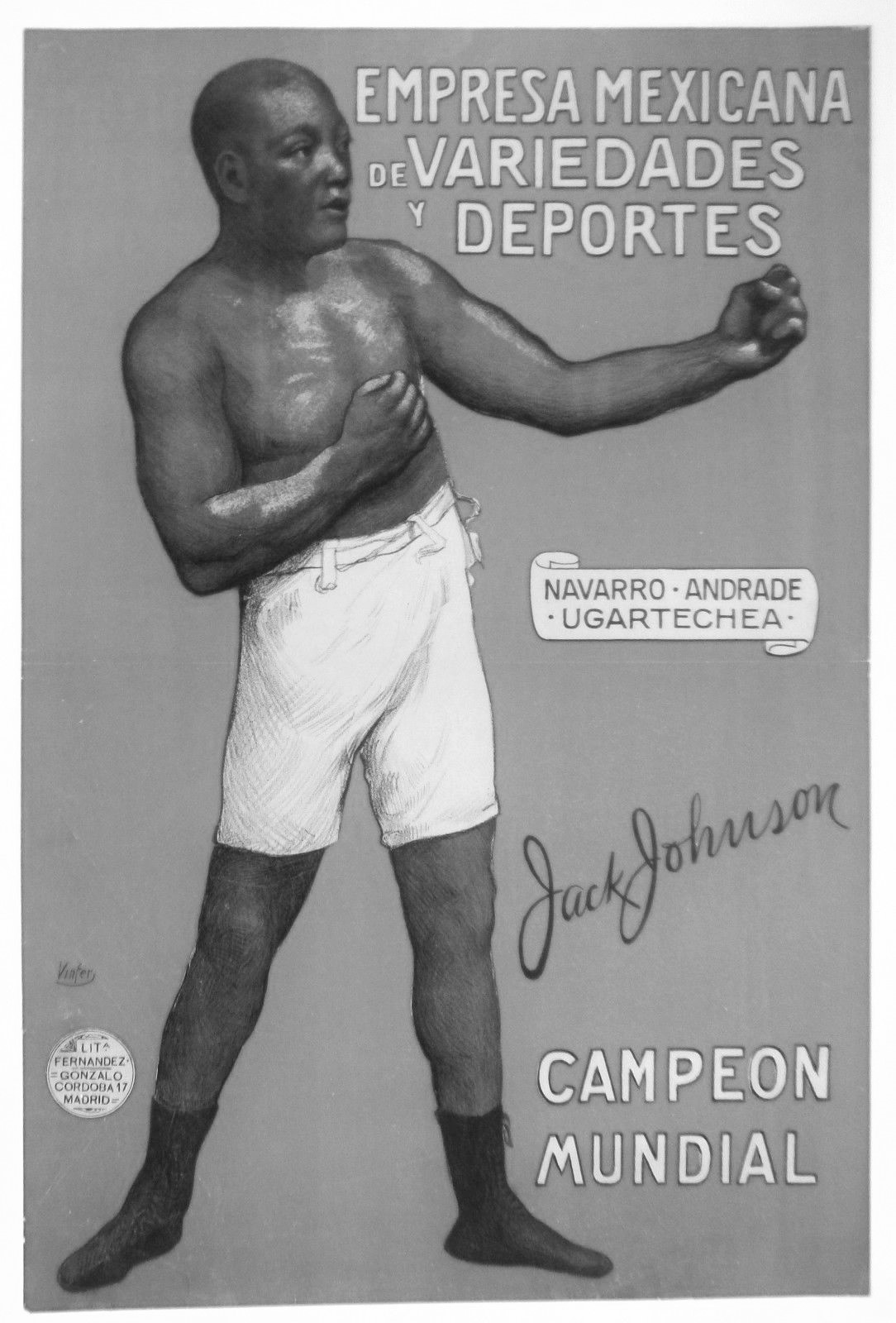

Any serious discussion of Jack Johnson is impossible without speaking of race. Not only was he the first black boxing heavyweight champion but all of his legal troubles and controversies stem largely from being a black man who refused to obey the era’s laws. During Johnson’s time, boxing remained segregated as white men held the world titles while black men could only reach the height of being named Negro champion. Boxing in Texas, Johnson’s home state, remained segregated until 1954 when the Court of Civil Appeals overturned a ban on mixed-race matches.[11] The segregation was partly due to the myth of black inferiority which, as related to boxing, portrayed blacks as cowardly and susceptible to body blows due to their supposedly weak mid-section. In 1906, American boxer Jim Jeffries was the heavyweight champion and like many, saw blacks as inferior. Jeffries refused to fight anyone who was not white, believing it an insult to the sport. After defeating all white opponents Jeffries retired to his farm, satisfied that no contender could challenge his boxing supremacy.

By 1908 the title belonged to Noah Brusso who fought as Tommy Burns.[12] Unlike Jeffries, Burns did not draw a color line and after years of pleading, Johnson finally received a title fight. Not that Burns was eager to fight Johnson. Burns demanded $30,000 to fight Johnson, confident no one would come up with it. It was not until Australian promoter, Hugh “Huge Deal” McIntosh, met his asking price that he fought Johnson, who received $5,000. Fighting in Sidney, Australia Johnson easily defeated Burns. The brutal beating forced police to stop the fight, ordering the cameras to stop recording and as a result no actual footage of Burns being knocked out exists—seconds before he is about to hit the canvas, the reel just stops.[13] American author and journalist Jack London attended the fight, likening it Armenian massacre. London wrote of Burns’s inability to hit Johnson as, “a dew-drop had more chance than he with the giant Ethiopian.”[14]

Johnson’s hometown of Galveston, Texas planned a parade to honor Johnson as the new heavyweight champion. However, upon discovering Johnson planned to attend the festivities with his white wife, officials cancelled all celebrations claiming they did not want to offend those who disapproved of Johnson’s marriage.[15] In another incident that occurred in Galveston during his early boxing career, police jailed Johnson and his opponent for twenty-one days. Though the arrest stemmed from boxing’s illegality within the state, the time Johnson spent incarcerated was long based on the offense. Compounding the time behind bars was Johnson’s $5,000 bond, a sum higher than what murder cases required.[16] After his arrest Johnson stated, “After this event, Galveston had no great charm for me and I again set out for new fields.”[17]

After the fight against Burns, there was an immediate outcry for a white boxer to defeat Johnson. Theoretically this boxer—the “Great White Hope”—would reclaim the title for the white race and reset the supposed proper order of racial hierarchy with the white man on top.[18] Jack London was one of the leading voices and believed the “Great White Hope” was none other than Jim Jeffries. “One thing now remains,” London wrote, “Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face. Jeff, it’s up to you!”[19] Jeffries did un-retire in 1910 to face Johnson in “The Battle of the Century”—a fight that Johnson, again, easily won. After the fight several blacks died in riots and lynchings across the U.S.

Noting the momentous event of Johnson’s victory and what it meant to their race, some in the black community believed those deaths, although tragic, were a suitable price to pay. The Chicago Defender wrote, “It was a good deal better for Johnson to win and a few Negroes to have been killed in body for it, than for Johnson to have lost and all Negroes to have been killed in spirit by the preachments of inferiority from the combined white press.”[20] Writing on the same event, decades after Johnson’s win and pointing out the dark absurdities of such lynchings, sportswriter Finis Farr sarcastically wrote, “That night six people were killed and scores wounded in serious rioting which broke out in both the North and the South. All this could have been avoided if Jack Johnson had not lived so high, or beaten Burns and Jeffries so badly, or even if he had shown the simple forethought to be born with a white skin.”[21]

In the end the court system defeated Johnson when none of the “Great White Hopes” could. In 1913 a second attempt from federal investigators to convict Johnson under the Mann Act proved successful. The Mann Act made illegal the interstate transportation of, “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”[22] In their first try (1912) to convict Johnson, federal investigators argued Johnson brought Lucille Cameron from Pittsburgh to Chicago as a prostitute, ignoring that Cameron was Johnson’s girlfriend. Though Cameron did not cooperate with authorities, her mother did. She considered her daughter insane as according to her logic, what else could explain her daughter’s want for a black man? Cameron’s refusal to cooperate coupled with her and Johnson’s marriage, led to the charges of abduction being dropped.[23]

Embarrassed by their failure, federal investigators dug deeper into Johnson’s past attempting to uncover evidence of his wrongdoings. Belle Schreiber, Johnson’s disgruntled ex-lover, provided the testimony allowing federal investigators to convict. According to Schreiber’s testimony, Johnson wired her $75 to travel from Pittsburgh to Chicago along with a promise of another $1500 upon arrival. The prosecution argued Johnson gave money to Schreiber to open a brothel. Since Schreiber worked as a prostitute and she and Johnson had a prior relationship, his sexual intentions were clear upon her arrival to Chicago—making it interstate transportation for prostitution.[24]

After an hour and a half of deliberation an all-white jury found Johnson guilty. Judge George Albert Carpenter sentenced Johnson to a year and a day in prison, stating his reasoning: “This defendant is one of the best-known men of his race, and his example has been far reaching, and the court is bound to consider the position he occupied among his people. In view of these facts, this is a case that calls for more than a fine.”[25] Although Johnson’s lawyers appealed and the judge reversed some chargers, by the time of re-sentencing Johnson had already fled the country. Recalling his decision to flee, Johnson wrote, “Had I been guilty of the charge which hung over me, I would have taken my medicine and said no more about it, but I was stung by the injustice of the whole proceedings and hurt to the quick to think that the prejudices of my fellowman and of my own countrymen, at that, could be so warped and so cruel.”[26] Johnson also saw the Mann Act as applied retroactively with the law not in existence during his time with Schreiber.[27]

Contrasting the view of the U.S. as a discriminatory country was Mexico—a country that some, including Johnson, saw as a place where a black man could escape racism and make a new life for themselves. This belief in Mexican reinvention is best exemplified through the story of George Goldsby. As the story goes, Goldsby was a former enlisted soldier in the U.S. Army. After finding himself in unspecified trouble around Texas, Goldsby fled to northern Mexico. Once there, he lived as a bandit before joining the Mexican military. With his military background and his natural leadership skills, Goldsby quickly moved up the ranks. Residents from his hometown of Vinita, Oklahoma remembered Goldsby, who was half black, as a man who could pass for Mexican. To further assimilate into Mexican society Goldsby changed his name to Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Yes, Pancho Villa—arguably the greatest general in Mexican history.[28]

Whether the story is true or not is beside the point. For our purposes the value of this story lies in the belief that a black man could escape from the U.S. and remake their life in Mexico, where not only would he be accepted but thrive. If believed, even anecdotally, that Goldsby could move to Mexico, become a military general on the verge of controlling the entire country, why could Jack Johnson not move to Mexico and simply be himself? Among the sources to publish Goldsby’s story was The Chicago Defender which was the nation’s most influential black newspaper.[29] With a readership of 500,000 per week, publishing these types of stories enhanced the notion that Mexico was a country where a black man could go to reinvent himself.

Johnson was not just ready to live out the rest of his life in Mexico but he actively encouraged other blacks to do the same. Obviously, the transition to Mexico would be easier for Johnson who as a wanted man in the U.S., had nothing to lose by going to Mexico. Beyond being free in Mexico, Johnson was financially prosperous with newspaper accounts stating, “Johnson is well fixed financially, has a signed contract with a Mexican syndicate, and we don’t believe he has this country to think about under the existing conditions, and perhaps the wrongs done to him here.”[30] Apart from operating a few nightclubs, Johnson owned a land company that advertised in black newspapers throughout the U.S. The advertisements read, “COLORED PEOPLE: You who are lynched, tortured, mobbed, persecuted and discriminated against in the boasted ‘Land of Liberty,’ The U.S.; OWN A HOME IN MEXICO: Where one man is as good as another, and it is not your nationality that counts but simply you.”[31] The advertisements added, “best of all there is [no] ‘race prejudice’ in Mexico and in fact, severe punishment is meted out to those who discriminate against because of his color or race. Neither is there censorship, espionage or conscription.”[32] But despite what Johnson thought or wanted to portray, the idea of Mexico having no racial prejudice was hardly true.

Because of his Mann Act conviction Johnson was already under U.S. surveillance which only intensified once he advertised what was essentially a call for blacks to escape their oppression by moving to Mexico. U.S. military intelligence also reported that Johnson spoke to large Mexican crowds assuring them that if or when the U.S. attacked Mexico, blacks would stand in solidarity and fight against the U.S.[33] “If you want us Mexico,” Johnson said, “we are ready to become your citizens and willing to do all that we can to make you a great power among the nations…we are ready to dwell among you and make you rich as we have made the southern white man rich”[34] But despite what he may have thought, Johnson was a controversial figure even among blacks for many of the same reasons whites vilified him—his lifestyle that included multiple marriages to white women.[35] In fact, Joe Louis who became heavyweight boxing champion in 1937 and promoted as the antithesis to Johnson, said, “when I got to be champ half the letters I got had some word about Jack Johnson. A lot was from old colored people in the South. They thought he disgraced the Negro.”[36]

Historian Randy Roberts argues that Johnson “exerted as much influence on his time as Booker T. Washington or W. E. B. Du Bois did.”[37] Coincidentally, Washington also complained about Johnson’s actions believing his brashness was counter-productive to the cause of black equality. Especially disconcerting to Washington was his belief that Johnson was the exact opposite of what a black man should act. Johnson was arrogant, free-spending, and defiant of white laws and customs.[38] Black newspapers were not always sympathetic to Johnson either with a columnist for Indianapolis’ Freeman writing of Johnson’s Mann Act arrest, “The cold hand of the law is reaching out for Mr. Johnson…and it looks to take the leading role in his future conduct. Why shouldn’t it, when the lives, liberty and happiness of over nine million Negroes are being antagonized and jeopardized by his folly.”[39] At the heart of these criticisms was the concern that while Johnson lived his life as he saw fit, other blacks suffered the consequences of his actions.

For U.S. officials whether blacks viewed Johnson in a positive or negative light was not their concern as reports from their spies continued to state his influence within Mexico. It certainly did not ease their nerves to read reports of twenty or so black men traveling to Mexico City to meet with Johnson and several of Carranza’s generals.[40] Other reports stated, “Jack Johnson, of pugilistic fame, has been spreading social equality propaganda among the Negroes in Mexico and has been endeavouring [sic] to incite colored element in this country.”[41] Another informant claimed to have infiltrated Johnson’s inner circle, spending a week with him and his family just to keep a close watch.[42] Others reports pegged Johnson as a “race man” and a socialist sympathizer who attempted to incite race rebellions. According to the U.S. State Department’s Federal Surveillance of Afro-Americans Papers, a person who knew Johnson stated, “I have become a friend of Jack Johnson, and can positively assert that he has sent money and written articles to aid the Negroes in their struggle in the U.S. He makes collections amongst Negroes and their sympathizers…He tried to go to the Antilles, especially Cuba, to foment a rebellion among the Negroes.” The source also stated that although Johnson did not consider himself a socialist he did call himself a “DEFENDER OF HIS RACE.”[43]

As previously noted, the politics of Mexico changed from 1915 to 1919. These changes affected their dealings with the U.S. Reports of Johnson’s antics took on a greater urgency as the U.S. could no longer count on Carranza to arrest Johnson. Certainly, Johnson’s time in Mexico and his relationship with both governments was not the sole reason for the deteriorating diplomacy between the U.S. and Mexico but it added to an already tense political climate. Compounding the Mexican Revolution’s unpredictability, the U.S. also had to worry about World War I. As such, multiple events added to the political uncertainty between the two countries.

With the Mexican Revolution’s outcome and its financial interests at stake, the U.S. had to choose a side to back. Initially, Woodrow Wilson supported Pancho Villa believing he could stabilize Mexico. Carranza influenced this decision as he refused to make concessions to Wilson, destroying U.S. owned property and even taxing American businessmen.[44] The relationship between Wilson and Villa soured when the former’s support reluctantly shifted to Carranza after Villa suffered a crippling defeat in the aforementioned Battle of Celaya and other battles.[45] Angered by the U.S. support of Carranza, in 1916 Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico and killed sixteen Americans.[46]

Subsequently, U.S. General John J. Pershing led the Punitive Expedition into Mexico attempting to capture Villa. Pershing’s troops faced local rancor and an unknown terrain adding to their mission’s difficulty. As Carranza would benefit from Villa’s capture, his troops at first helped Pershing though he remained cautious, believing the U.S. could use the pursuit of Villa as an excuse to make war against Mexico. As time passed and Villa remained free, it became harder for Carranza to support Pershing with public opinion turning towards Villa and against the U.S. military being in Mexico. This change of public opinion affected Carranza’s troops with some helping Villa and his troops.[47] Even though it was a revolutionary war, Carranza’s troops were in an odd predicament of attempting to capture their fellow countrymen for the benefit of what many saw as a foreign invader. Frank McLynn captured the inner struggle faced by some of Carranza’s troops, writing, “In the village of Matachic there was a revolt by the garrison who demanded to be allowed to join Villa and defend Mexico’s sacred soil against the yanquis.”[48]

As Pershing moved deeper into Mexico and his troops grew upwards of 7,000, experts in Washington saw war as inevitable.[49] Preliminary war plans included a naval blockade of all Mexican ports along with military occupation of several states in Northern Mexico. Helping enforce these plans would be 250,000 troops.[50] Attempting to avert war, U.S. and Mexican representatives met in search of an agreement. An initial proposal stated U.S. troops would stay in Mexico so long as their presence was necessary. Carranza objected, claiming the proposal offered no exact timeline for U.S. troop withdrawal, potentially making their stay indefinite.[51] Negotiations concluded and on February 5, 1917, Pershing and his troops left Mexico. Upon hearing the news, Villa allegedly said, “Adios gringos, Que les vaya bién!”[52] U.S. troops never captured Pancho Villa.

World War I caused further strain in U.S., Mexico relations. Coincidentally, an unnamed source in a military attaché report claimed throughout World War I, Johnson remained Pro-German. His reasoning was simple: “The Germans treat me as a man and my wife as a lady.”[53] Johnson claimed to have intelligence of German submarines off the coast of Spain. When asked by the unnamed source why he did not use the information to leverage a deal on his Mann Act conviction, Johnson said, “Oh, to hell with them, I would not believe any promise they would have made me.”[54] The truthfulness of Johnson’s claim is unknown.

In another World War I related incident, in early 1917, British officials deciphered a telegram sent from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to Mexico’s minister to Germany. The Zimmerman Telegram stated Germany’s intent to begin “unrestricted submarine warfare” and hoped the U.S. would continue its neutral standing. However, if the U.S. abandoned its neutrality and entered the war, Germany offered Mexico the return of its land—lost through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—so long as Mexico joined Germany’s war effort.[55] Figuring the British were attempting to bring them into their fight against Germany, the U.S. initially saw the telegram as a fake. Zimmerman erased all doubts when he confirmed its authenticity.[56]

Though Mexico never acted on Germany’s offer, the Zimmerman Telegram reawakened the U.S.’s lingering fears of Mexico attempting to regain the territory it lost during their war in 1846. Some see the Plan de San Diego as partly motivating the Zimmerman Telegram. The plan, “called for a general armed uprising on February 20, 1915, to proclaim independence in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California.”[57] The uprising would be fought by an army made up of blacks, Japanese and Mexican-Americans who would slay all Anglo men over the age of sixteen. Plans also stated that after the five states’ independence, they would consider annexation back to Mexico.[58] Around the same time, racial violence erupted in south Texas as Mexicans, called Sediciosos, caused havoc by stealing livestock, destroying bridges and railroad tracks and killing Anglo farmers.[59] With the Sedicioso attacks coinciding with the Plan de San Diego’s discovery, they appeared related though no historical records can prove it.[60]

As World War I continued with the U.S. as Britain and France’s main oil supplier, concern grew over Mexico who had the largest known oil reserves. In 1918 Carranza increased taxes on oil companies which, when combined with the increasing demands, caused oil prices to triple within eight months. Attempting to stabilize prices, the U.S. State Department suggested occupying the Mexican oil fields with the help of 6,000 troops. In the end, Woodrow Wilson decided against it, taking the advice of Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels who saw such actions unjustified.[61]

This was the political atmosphere into which Johnson arrived in the early days of April 1919. He quickly embraced the chaotic times as “the revolutionary atmosphere of Mexico worked on him like a tonic.”[62] Undoubtedly, the warm welcome Johnson received made his acclimation to Mexico easier as a crowd of thousands gathered for his arrival at the train station. Music blared as the people chanted in unison, “Viva Johnson!” Swept away by such emotion, even children shouted their approval—“Bravo Jack!”[63] Mexico bordering the U.S. also influenced Johnson’s decision to move there from Spain, stating, “I accepted the opportunity to go to Mexico City, with deep satisfaction, because it would bring me nearer home and might be an important step in ultimately ending my exile one way or another.”[64] Though Johnson felt the pressure of living in exile, one could not tell by looking at his professional career that, outside of boxing, bloomed.

Through his connections with the Mexican government, Johnson taught self-defense to high-ranking military officials.[65] Besides taking part in strongman and bullfighting exhibitions, there were plans to make Johnson a movie star. Johnson would play the role of Mexican adventurer, Pedro Cronolio. The movie, based on the olden days of the Mexican border, was a love story that included the search for gold and the eventual, “sudden rise to the highest position of human attainment in the Mexican government.”[66]

Though the movie was probably not made, it shows the lengths to which Johnson had become a part of Mexican society. But despite his seemingly easy integration into Mexican culture, Johnson held an ambiguous place within their society, acting more as a symbol on two fronts. First, Johnson was a link to U.S. commercial culture as he helped spread boxing’s popularity from the border regions of Mexico, where the sport was much more popular, to the interior of the country. Second, Johnson was a symbol of anti-Americanism, therefore developing a greater following among Mexican fans.[67] Further, some of these Mexicans fans saw Johnson as a victim of “perverted American Justice,” treating him like a brother fighting against the same oppression they faced.[68] However perceived, Johnson had a certain amount of favor in Mexico and its people as he moved “about the broad boulevards of the capital in a late-model automobile, he was as much a fixture in the city as the Spanish colonial architecture that gave the capital its distinctiveness.”[69]

Even apart from his marriages to white women within a society that deemed such actions unacceptable, Johnson lived a reckless life. Known for drinking, womanizing, driving fast cars and getting into street fights while in the U.S., Johnson did not change his style while in Mexico. Knowing he had greater leeway than just about any other person in Mexico, Johnson continually found himself in problems though his connections with the government kept him from being charged. But as he had been in the U.S., Johnson remained the center of attention, carousing with cientificos, military men and important members of Mexico’s mining industry.[70]

Even outside of Mexico City, Johnson’s celebrity was immense. An example of his popularity came during his travels to Sonora when Yaqui Indians stopped the train he was riding. According to Johnson, Yaqui Indians used the revolution as an excuse to pillage railroads.[71] Fortunately, Johnson defused the situation by explaining who he was. Though the Yaquis were at first hesitant to believe him, they eventually realized he was, in fact, Jack Johnson, and released the train. Johnson recalls the experience,

At first they doubted that I was actually Jack Johnson. I had no idea, however, that they had ever heard of me, for I did not expect that these savages had much knowledge of what was going on in the world. I was surprised to find out that they did know who I was, and for a moment, when they were convinced of my identity, it appeared that they were going to stage a wild demonstration in my honor. They manifested more interest and excitement over my appearance than they had in the promise of loot. Leaders of the band were profuse in their apologies for molesting the train, declaring that had they known I was aboard, they would not have thought of stopping the engine. What loot they had taken they restored to the passengers and told us that we might go on. I mingled freely with the Yaquis and when our train pulled out they were in a most friendly mood. I later was heaped with thanks by the passengers who had good reason to believe that had the Indians carried out their original intentions, they might not have lived to relate their experiences.[72]

Despite his popularity Johnson’s good times in Mexico waned with Carranza’s assassination. In June 1919 Obregón announced his candidacy for president, expecting Carranza’s support since, as his top general, Obregón defeated Carranza’s military opposition. But Carranza, at least publicly, believed a civilian should succeed him as president and not a military man like Obregón.[73] Privately, Carranza attempted to stay in power, naming Ignacio Bonilla his successor who would essentially act as his puppet.

As president, Carranza made many enemies whom Obregón won over. During brief campaign stops, Obregón pointed out his revolutionary successes telling audiences he had overcome, “rain, wind, Orozco, Huerta, Villa and Zapata”—an obvious inference that Carranza would not stand in his way.[74] To a cheering crowd Obregón vowed, “Before the bearded old man can rig the election, I will rise against him.”[75] Sensing support turning against him, Carranza fled the capital in May of 1920. Under his troop’s protection, whom he believed loyal, Carranza planned to move deep into the mountains of Tlaxcalantongo and re-organize. As it turned out, the troops’s loyalty did not lie with Carranza and his plans to fight Obregón never came to fruition. A subordinate officer killed Carranza as he yelled, “Viva Obregón!”[76]

In the midst of the chaos, Johnson left Mexico City after Carranza informed him of potential violence. “Making his plans for a fast getaway,” wrote Johnson’s biographer Finis Farr, “Carranza was thoughtful enough to send warning to Johnson that the outgoing President’s friends would be dangerously unpopular with Obregón and his followers.”[77] Johnson did not mention Carranza’s warning in his autobiography but stated that as violence increased in Mexico City, he fled for Baja California. With plans of increasing tourism through boxing promotions, Baja California’s governor Esteban Cantú encouraged Johnson’s relocation.[78] Johnson did put on several fights, as he stated, “as soon as I reached Tia Juana [sic], I found that several bouts had been arranged for me. The sportsmen, tourists and others apprised of my coming awaited me anxiously and gave me quite a welcome.”[79] More than likely, these fights were against low-level opponents that did not require serious training. This was not necessarily Johnson’s fault as boxing was a relatively new sport in Mexico. “It was difficult for me to find opponents,” Johnson noted on the difficulty in finding opposition, “and there were long stretches of time during which I was idle.”[80] Even if opponents were available, it is unclear how committed Johnson remained to competing at a high-level. Besides, being close to forty years old, living the good life in Mexico and operating a successful night club in Tijuana was not the lifestyle conducive to being in shape to even fight a decently skilled boxer. Although Johnson spoke of fighting Jack Dempsey, who after defeating Jess Willard became the heavyweight champ, no fights against serious contenders ever materialized.[81]

Understandably, Johnson’s thoughts fluctuated between remaining in Mexico and returning to the U.S. With his legal troubles looming, Johnson spoke of returning to the U.S. but only under the right conditions—presumably, if authorities reduced his prison sentence. But with all he said and did while in Mexico, U.S. authorities refused to even consider leniency, continuing to demand Johnson’s unconditional surrender. With no deal in place Johnson remained in Mexico, making money from his various business ventures outside of boxing. Carranza’s death, which drastically altered the Mexican government, changed Johnson’s plans. Trying to keep his own position, Governor Cantú, who backed Johnson’s relocation to Baja California, reneged on his support. Increasingly without allies, Johnson found his nightclub shuttered and unable to box anywhere in the country.[82]

Trying to add further distance between himself and Johnson while attempting to gain favor from both Mexican and U.S. governments, Cantú informed U.S. agents that Johnson was no longer welcomed and would be happily turned over to proper authorities at their request. Cantú claimed to have caught Johnson dealing in illegal transactions and therefore, his deportation was necessary.[83] It is unclear what illegal dealings Johnson took part in, if any. More than likely, Cantú wanted to get rid of Johnson who as a friend of the deposed and assassinated president, had become politically toxic. U.S. authorities thought it suspicious that Cantú would suddenly turn on Johnson and declined his offer.

As Johnson’s time in Mexico drew to an end, the best he could hope for was a negotiated return to the U.S. A year in a U.S. prison was a better choice than the harsh realities that may have come Johnson’s way as an unwanted guest in Mexico. Assassinating a standing president was not out of the norm in the revolution’s violence so it was likely that Johnson felt his fame had reached its limits of protection. Johnson reached out to U.S. authorities asking that in return for his surrender, they treat him with dignity, meaning no handcuffs and having a black officer transport him to Chicago. Authorities refused to negotiate—besides giving their word to treat Johnson respectfully, there were no other assurances.[84]

On July 20, 1920, roughly a month after Carranza’s assassination, Johnson turned himself over to U.S. authorities in San Diego, California. After saying his goodbyes and shaking hands with several Mexican officials, Johnson presented his passport and turned himself over to authorities. Cameras and reporters were present for Johnson’s statement: “It sure is good to get back in the U.S. again. I am returning voluntarily, for the Mexican Government had issued no deportation order against me, as was reported some weeks ago, and I could have remained in Tiajuana[sic] as long as I was willing to obey the laws of Lower California. But for a long time I have wanted to return and get my troubles adjusted.”[85]

Johnson never admitted to being forced out of Mexico. Despite all that transpired between the U.S. and Johnson, he felt a sense of relief in reuniting with loved ones. “No man, unless he has been through the experience,” Johnson explained, “can realize the relief it brings when he returns to his country after being in exile for five years.”[86] As for the anti-U.S. statements he repeatedly made while in Mexico, Johnson simply stated, “You know I have changed my allegiance a number of times, but I am still an American.”[87]

Johnson served his sentence in Kansas’ Leavenworth Prison where he continued to box. His bouts, which attracted many spectators, took place in a ring especially built inside the prison. Jack Johnson recalled one event as, “the seating capacity as entirely exhausted…prison bands were out in force and played march tunes as the spectators took their seats…several special guests were present and that among them were well known sportsmen and newspaper writers.”[88] After his prison sentence, Johnson continued living life as he wished. He remained married to a white woman, kept drinking, and driving fast. Johnson worked as a vaudevillian actor, putting on boxing exhibitions and performing comedy along with members of an acting troop, of which he was the only black member. Johnson also resumed his boxing career even fighting in Ciudad Juárez in 1926. However, this was no longer the same Jack Johnson nor the same tumultuous Mexico of the revolution.

By 1926 the revolution’s overt violence that boiled over during Johnson’s time, reduced to a simmer. After Carranza’s assassination, Obregón became president on December 1, 1920 and served his full term, a rarity in the violent times of Mexican politics—violence to which he greatly contributed. Before his term expired, Obregón likely ordered his old rival Pancho Villa killed, fearing he would un-retire and lead another uprising.[89] Before his assassination, Villa and Obregón worked out an agreement that in exchange for Villa laying down his weapons, he could retire to a hacienda in the outskirts of Hidalgo del Parral, Chihuahua. In exchange, the government gave Villa and his men amnesty, paid for his hacienda and the salaries of his many bodyguards.[90]

On July 20, 1923, driving through the streets of Hidalgo del Parral, Villa’s car stopped at an intersection. The streets were empty except for a man selling candy who yelled, “Viva Villa!”—a seemingly innocuous, admiring phrase that Villa must have heard tens of thousands of times. The phrase was the signal to open fire as gunmen emerged from surrounding buildings and shot at Villa’s car.[91] Pancho Villa, the “Centaur of the North,” as they called him, was dead. As for Obregón, he too would meet a violent death. When the 1928 presidential election arrived, Obregón ran for and won a second term. Before he assumed office an assassin, disguised as an artist hired to paint his portrait, killed him—shooting Obregón five times in the face.[92]

Obregón was forty-eight at the time of his death, the same age Johnson was when he fought in Ciudad Juárez. Facing Bob Lawson, Johnson was clearly past his prime. Though there is no video of Johnson’s fight in Ciudad Juárez, one can imagine the sad sight of one of the greatest boxers reduced to nothing more than a club fighter with name recognition. Though scheduled for twelve rounds, Johnson could not continue at the start of the eighth. The Chicago Defender wrote of the loss, “Just as the gong sounded ending round seven Johnson hit the floor with a crash. Lawson having connected with the former champ’s body via a heavy blow. Johnson could not rise at the beginning of round eight and Lawson was given the fight on a technical knockout.”[93] Johnson fought until he was close to sixty years old and counting his fight in Ciudad Juárez, he lost seven of the last nine fights.

Jack Johnson’s life ended in an accident which oddly encompassed his life’s racial troubles. The event occurred close to thirty years after the Sanborn incident in which Johnson’s military friends come to his defense over the refusal of service. In Jim Crow south, government took a different stance when deciding whether blacks would be served, and if so, where they could eat. In 1946, Johnson and an associate named Fred Scott stopped at a diner near Raleigh, North Carolina. “They told us we could eat in the back or not at all,” Scott remembers. “We were hungry and the food had already been served so we ate.”[94]

Johnson’s anger increased with each mile he drove away from the diner. Already a notoriously fast driver, Johnson’s anger caused him to rapidly pick up speed. Near Franklinton, North Carolina, Johnson lost control of his car, ramming into a telephone pole. Though rushed to the closest black hospital, Johnson did not survive. Jack “The Galveston Giant” Johnson died aged sixty-eight. His funeral took place in Chicago with thousands in attendance and thousands more waiting outside the church to pay their respects.[95] Johnson lived a remarkable life that even he found incredible: “How incongruous to think that I, a little Galveston colored boy should ever become an acquaintance of kings and rulers of the old world…What a vast stretch of the imagination to picture myself a fugitive from my own country, yet sought and acclaimed by thousands in nearly every nation of the world!”[96] Johnson’s high acclaim among boxing enthusiasts does not simply stem from being the first black heavyweight champion as his talent and skill were remarkable. Nat Fleischer, boxing historian and founder of Ring Magazine, stated, “After years devoted to the study of heavyweight fighters, I have no hesitation in naming Jack Johnson as the greatest of them all.”[97]

Jack Johnson’s time in revolutionary Mexico showed the differences in how U.S. and Mexico viewed race. Ultimately what occurred within each country and between them, influenced their racial attitudes—at least as they related to Johnson. Depending on Mexico’s political circumstance, Johnson was either a welcomed guest of the government or as someone who overstayed the welcome given to him by the earlier, corrupt government. The U.S. saw Johnson as either someone who refused to conform to societal standards or as a disloyal citizen who actively recruited others to follow his dissent. Therefore, his standing in the U.S. never fluctuated between two extremes as it did in Mexico.

In recent years there has been a push by politicians and the some in the public for Johnson to receive a presidential pardon from his Mann Act conviction.[98] There is no explanation why the pardon has not been granted or if it ever will. Even today, in what some believe is a post-racial society, Johnson remains a controversial figure. Only recently has his hometown of Galveston attempted to embrace the memory of Johnson, likely the most famous person born in that city. It was not until 2012 that Johnson had a park and statue dedicated to his memory. An earlier statue of Johnson became unrecognizable after being damaged by bullet holes and severe weather. Michael Hoinski of Texas Monthly writes of the park’s importance, “Jack Johnson Park exists not just as a truce with Johnson, but also as a way to empower Galveston to face its past as a slave market and its present as a tourist destination.”[99] Granting a presidential pardon to Johnson could work in the same way, forcing the U.S. to face its discriminatory past that is never as neatly tucked away in history as some would like to believe. A discrimination that always seems to show itself no matter how post-racial one may think the society we now live in is.

[1] Theresa Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012), 226.

[2] Ibid., 226.

[3] For a slightly different account of the incident see Randy Roberts, Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes (New York: Free Press, 1983), 211.

[4] U.S. Congress. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Investigation of Mexican Affairs. (Washington D.C.: Washington Government Printing Office, 1920), 1113 – 1114.

[5] Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner, 201.

[6] “Bar Jack Johnson: Carranza Men Anxious to Stop Fight for Villa’s Profit in Mexico” New York Times, January 14, 1915.

[7] Willard defeated Johnson who claimed to have thrown the fight, believing that in doing so, authorities would show leniency and allow his return to the U.S. without facing imprisonment. Johnson stated, “Preceding the Willard fight it was hinted to me in terms which I could not mistake, that if I permitted Willard to win, which would give him the title, much of the prejudice against me would be wiped out.” The perceived hints did not materialize and Johnson continued living in exile. See Jack Johnson, In the Ring and Out (Chicago: National Sports Publishing Company, 1927), 101.

[8] Regarding his friendship with Carranza, Johnson stated, “Carranza tendered me his friendship and made every effort to make my stay in the Mexican Republic a pleasant and comfortable one, even going so far as to provide me with escorts of soldiers when I had occasion to travel in sections of the country infested by bandits or revolutionists.” See Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 111.

[9] Ibid., 112-113.

[10] Gerald Horne wrote of Johnson: “He had committed two major transgressions for a black man – consorting with Euro-American women and allying with foreign powers.” See Gerald Horne, Black and Brown: African Americans and the Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920. (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 37.

[11] Francine Sanders Romero, “‘There Are Only White Champions’: The Rise and Demise of Segregated Boxing in Texas,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 108, No. 1 (Jul., 2004): 26-41.

[12] It was not uncommon for boxers from this time to fight under aliases. It is unclear why they did so but one can assume that the varying legality of boxing from place to place had something to do with it. Today, the only reason a fighter would fight under a different name is to escape state regulations on how often a boxer can fight due to health concerns. See Geoffrey Gray, “Boxing; Boxers Who Are Losers; Promoters Who Love Them” New York Times, May 10, 2004.

[13] Ken Burns, Unforgiveable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. Florentine Films Inc., DVD. PBS Home Video, 2004.

[14] Finis Farr, “Black Hamlet of the Heavyweights” Sport Illustrated, June 15, 1959.

[15] Randy Roberts, Papa Jack: Jack Johnson and the Era of White Hopes. (New York: Free Press, 1983), 71.

[16] Randy Roberts, “Galveston’s Jack Johnson: Flourishing in the Dark.” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 87, No. 1 (Jul., 1983): 37-56.

[17] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 43.

[18] Howard Sackler based his Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award winning play, “The Great White Hope” on Johnson’s life with the lead character named Jack Jefferson. In 1970 the play was adapted a movie by the same name with James Earl Jones playing the lead role.

[19] Farr, “Black Hamlet of the Heavyweights.”

[20] Quoted from the Chicago Defender via Denise C. Morgan, “Jack Johnson Versus the American Racial Hierarchy.” Race on Trial: Law and Justice in American History, ed. Annette Gordon-Reed (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 82.

[21] Farr, “Black Hamlet of the Heavyweights.”

[22] SIXTY-FIRST ‘CONGRESS. SESS.’ II. CHs. 393-395. 1910. http://legisworks.org/sal/36/stats/STATUTE-36-Pg825a.pdf

[23] Gordon-Reed, Race on Trial: Law and Justice in American History, 89.

[24] Ibid., 92.

[25] Farr, “Black Hamlet of the Heavyweights.”

[26] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 83-84.

[27] Ibid., 83.

[28] “General Villa is George Goldsby, Lived in Vinita.” The Chicago Defender, March 14, 1914, 2.

[29] Other newspaper accounts of Goldsby as Villa were the New York Age and the Indianapolis Freeman. See Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner, 312.

[30] “Jack Johnson Idolized in Mexico,” The Chicago Defender, May 10, 1919. 11.

[31] Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner, 227. For a slightly different variation of same ad see Roberts, Papa Jack, 212.

[32] Horne, Black and Brown, 2.

[33] Roberts, Papa Jack, 212.; Horne, Black and Brown, 35.

[34] Horne, Black and Brown, 28.

[35] Denise C. Morgan, “Jack Johnson: Reluctant Hero of the Black Community,” Akron Law Review 32, (Jan., 1999): 529-791.

[36] Patrick Myler, Ring of Hate, Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling: The Fight of the Century (New York: Arcade Publishing, 2005), 21.

[37] Roberts, “Galveston’s Jack Johnson: Flourishing in the Dark,” 37.

[38] Geoffrey C. Ward, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 145.

[39] Ibid., 181.

[40] Gerald Horne and Margaret Stevens, “Eureka! The Mexican Revolution in African American Context, 1910-1920.” War Along the Border: The Mexican Revolution and Tejano Communities, ed. Arnoldo De León (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2012), 303.

[41] Horne, Black and Brown, 32.

[42] Ibid., 30.

[43] Ibid., 29.

[44] Stuart Easterling, The Mexican Revolution: A Short History 1910-1920 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012), 78

[45] One of the battles that occurred after Celaya was the Battle of León. It was there that Álvaro Obregón lost his right arm after a shell exploded. Believing that he was on the verge of dying, Obregón attempted to kill himself, but his revolver did not shoot—twice. His assistant had cleaned his weapon earlier and forgot to reload it. See Ibid., 124.

[46] Punitive Expedition in Mexico, 1916-1917. U.S. Department of State Archive.

[47] Frank McLynn, Villa and Zapata: A History of the Mexican Revolution (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2002), 326.

[48] Ibid., 326.

[49] Ibid., 325.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Punitive Expedition in Mexico, 1916-1917. U.S. Department of State Archive.

[52] Clarence C. Clendenen, “The Punitive Expedition of 1916: A Re-Evaluation,” Arizona and the West, (Winter, 1961): 319.

[53] Horne, Black and Brown, 30.

[54] Ibid., 30.

[55] National Archives and Records Administration, Zimmerman Telegram – Decoded Message. Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State, 1756 – 1979.

[56] Horne, Black and Brown, 156.; Arnoldo De León, War Along the Border, 293.

[57] Charles H. Harris III and Louis R. Sadler, “The Plan of San Diego and the Mexican-U.S. War Crisis of 1916: A Reexamination,” The Hispanic American Historical Review, (Aug., 1978): 381.

[58] Ibid., 382.

[59] Benjamin Johnson, “The Plan de San Diego Uprising and the Making of the Modern Texas-Mexican Borderlands.” Continental Crossroads: Remapping U.S.-Mexico Borderlands History, ed. Samuel Truett and Elliott Young (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 273.

[60] Authorities discovered the Plan de San Diego with the arrest of Basilio Ramos Jr. who carried a copy of the plan.

[61] David Stevenson, With Our Backs to the Wall: Victory and Defeat in 1918 (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), 361.

[62] Horne, Black and Brown, 25.

[63] Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner, 224.

[64] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 111.

[65] “Jack Johnson Rolling High: Now Physical Instructor of Mexican Generals, with High Prestige” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1919.

[66] Horne, Black and Brown, 31.

[67] Runstedtler, Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner, 224.

[68] Roberts, Papa Jack, 211.

[69] Horne, Black and Brown, 25.

[70] Ibid., 32.

[71] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 115.

[72] Ibid., 115-116.

[73] McLynn, Villa and Zapata, 380.

[74] Ibid., 381.

[75] Ibid., 380

[76] “Obregón Announces ‘Cowardly Murder’ of Deposed Leader.” El Paso Herald, May 22, 1920.

[77] Finis Farr, Black Champion. (Greenwich, Conn.: Fawcett Publications, 1969), 176.

[78] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 114.

[79] Ibid., 120.

[80] Ibid., 114.

[81] Attesting to Johnson’s popularity in Mexico, there were preliminary talks of a bout between him and Jack Dempsey. The fight would be part of Mexico’s centennial celebration of independence. Because of his popularity a New York Times article stated that most sportsmen in Mexico believed that Johnson would win–despite being Dempsey’s elder by close to twenty years. The two never fought but the odds of Johnson beating Dempsey in their respective stages of their careers was highly improbable. See “Mexico Wants big Bout: Officials Seek Dempsey-Johnson Fight While Centennial Is On.” New York Times, August 5, 1921.

[82] Roberts, Papa Jack, 213.

[83] Ibid., 213-214.

[84] Ibid., 214.

[85]“Seize Jack Johnson at Mexican Border.” New York Times, July 21, 1920. 13.

[86] Roberts, Papa Jack, 215.

[87] Ibid., 215.

[88] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 131.

[89]Easterling, The Mexican Revolution, 140.

[90] Ibid., 137-138.

[91] McLynn, Villa and Zapata, 393.

[92] Ibid., 398.

[93] “Lawson Knocks Out Jack Johnson.” The Chicago Defender. June 5, 1926. 11.

[94] Burns, Unforgivable Blackness. DVD.

[95] Ward, Unforgivable Blackness, 448.

[96] Johnson, In the Ring and Out, 25.

[97] Farr, “Black Hamlet of the Heavyweights.”

[98] Barbara Antoniazzi. (Un-Forgivable Blackness and the Oval Office. Jack Johnson and Henry Louis Gates at the Postracial White House. Race, Gender & Class. Vol. 17 No. ¾, Race, Gender & Class 2010 Conference. 9-18.

[99] Michael Hoinski. “Galveston Moves One Step Closer to Embracing Jack Johnson.” Texas Monthly, July 2, 2012.

Originally published on IBRO, International Boxing Research Organization.